The Howard Greenberg Gallery’s exhibition, A Response to Wonder, brings together three trailblazing photographers—Charles Jones, Karl Blossfeldt, and Edward Weston—in an exquisite exploration of natural forms. Running from December 5, 2024, to January 18, 2025, the show is a meditative journey into the intersection of organic beauty and artistic vision. Each artist, though rooted in a distinct era and context, contributes to a harmonious conversation about humanity’s enduring fascination with the natural world.

Charles Jones: Elegance in Cultivation

Charles Jones, a gardener-turned-photographer, transforms the everyday into the extraordinary. His gold-toned gelatin silver prints of vegetables, fruits, and flowers resonate with a quiet dignity. The humble pea pod and the onion bulb become, under his lens, emblems of life’s symmetry and purpose. The timelessness of Jones’s work, created between 1895 and 1910, belies its near-forgotten history—rediscovered only decades later in a trunk at a London market. His minimalist compositions, where subjects float against dark, neutral backdrops, anticipate modern photographic techniques while paying homage to the purity of his subjects. The organic simplicity of Jones’s work bridges photography with an almost sculptural sensibility, turning root vegetables into enduring symbols of the earth’s quiet abundance.

Karl Blossfeldt: Nature’s Architect

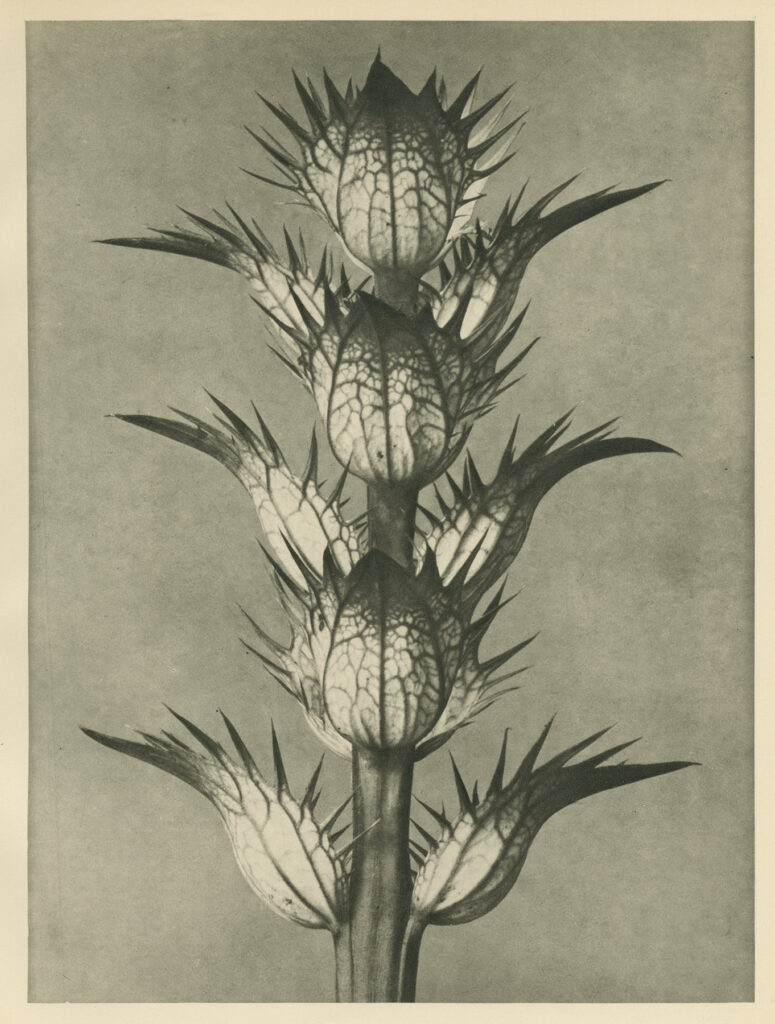

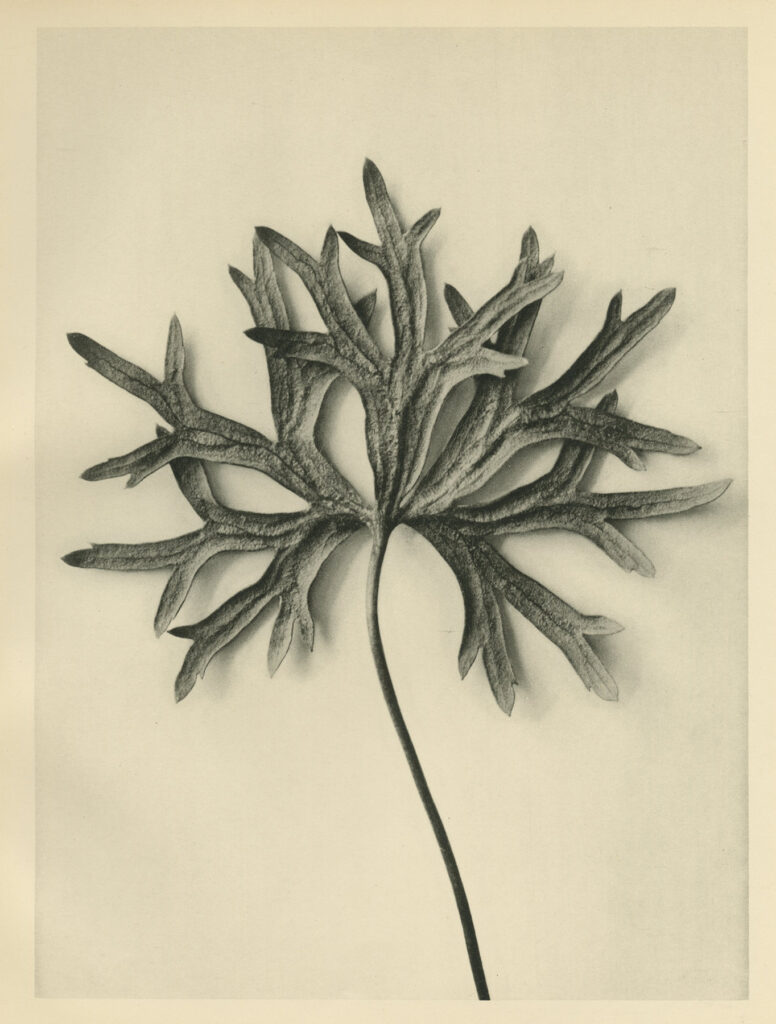

Karl Blossfeldt’s work forms the heart of A Response to Wonder, inviting viewers into a magnified world of nature’s designs. Blossfeldt’s methodical approach reveals plants not just as organisms but as blueprints of perfection. His intricate black-and-white photographs of seed pods, tendrils, and leaves celebrate nature as the ultimate designer.

Using custom-built cameras that magnified his subjects up to 30 times their size, Blossfeldt captures botanical structures with unparalleled precision. Works like Adiantum Pedatum (Maidenhair Fern) unveil the subtle curvatures and symmetries often overlooked by the naked eye. Blossfeldt’s imagery resonates with both the scientific and the poetic—natural forms echo the spirals of cathedrals, the elegance of Art Nouveau, and the enduring order within chaos.

Edward Weston: The Modernist Gaze

In contrast to the other two artists, Edward Weston’s lens seeks abstraction within realism. His gelatin silver prints, often hailed as icons of the modernist movement, strip natural objects down to their elemental forms. A cabbage leaf, under Weston’s gaze, becomes a flowing terrain of undulating ridges; a pepper transforms into a sensual sculpture of shadow and light.

Weston’s focus on texture and form, especially in works like Pepper No. 30, defies the boundaries of nature photography. His exploration of surface, contour, and shadow elevates everyday objects into profound meditations on structure and impermanence. The juxtaposition of his works with those of Jones and Blossfeldt reveals a shared awe for nature’s intricacies, even as Weston’s modernist aesthetic pushes the boundaries of interpretation.

Intersections and Inspirations

The brilliance of A Response to Wonder lies in its curatorial precision. While Jones, Blossfeldt, and Weston differ in technique and philosophy, their works share a reverence for nature’s design. Together, they chart a continuum of photography’s evolution—from documentation to abstraction, from celebration to reinterpretation.

This conversation across time and style invites viewers to question their relationship with nature. How do we see the world around us? What details escape us in our haste? Each photograph in the exhibition challenges us to slow down, observe, and reflect on the universal rhythms connecting all living things.

Final Thoughts

A Response to Wonder* is more than an exhibition—it is an ode to the transformative power of observation. In an era increasingly disconnected from the natural world, the works of Jones, Blossfeldt, and Weston remind us of nature’s enduring artistry. Through their lenses, the mundane becomes magnificent, the overlooked becomes sacred. This masterful exhibition offers a timely reflection on the elegance of the organic and the human capacity to celebrate it through art. For anyone seeking a moment of stillness and awe amid the chaos of modern life, A Response to Wonder is a gift that lingers long after you leave the gallery.

About the Photographers

Charles Jones (1866–1959) remains one of photography’s most enigmatic figures, his work only brought to light after being discovered by a collector at a London street market in 1981. Born in England and trained as a gardener, Jones gained public recognition during his lifetime for his horticultural expertise rather than his artistic endeavors. Between 1895 and 1910, he delved into photography, producing a remarkable series of gold-toned gelatin silver prints that immortalized vegetables, fruits, and flowers.

Jones’s approach was groundbreaking for its time. He isolated his botanical subjects from their natural environments, placing them against neutral or dark backdrops, a technique that emphasized their forms and textures with extraordinary clarity. This unique style anticipated the works of later photographers like Edward Weston and Karl Blossfeldt, whose Modernist images gained prominence in the 1920s and 1930s.

Despite the brilliance of his work, Jones was not recognized as a photographer during his lifetime. It is believed he pursued photography as a private exploration, sharing little of this passion with his family or friends. Adding to his mystery, Jones left behind no negatives, journals, or personal papers, and he lived a reclusive life until his death in 1959. His legacy was further cemented with the 1998 publication of Plant Kingdoms: The Photographs of Charles Jones, featuring a foreword by Alice Waters, which introduced his extraordinary vision to a wider audience.

Karl Blossfeldt (1865–1932): Nature’s Sculptor

Karl Blossfeldt (1865–1932), a German sculptor and photographer, is celebrated for his magnified close-up photographs of plants, which were first introduced to the world in his seminal 1928 monograph Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Nature). Blossfeldt’s artistic journey began in the 1890s under the mentorship of Moritz Meurer. From 1890 to 1896, he traveled across Europe and North Africa, capturing botanical specimens that became the foundation of his life’s work.

Blossfeldt began teaching in 1898 and used his photographs as educational tools, meticulously cataloging plant specimens and their names. By the 1920s, his photography gained recognition for its artistic significance. His images, characterized by their precision and sharp focus, stood in stark contrast to the soft-focus photography popular during his time.

Blossfeldt’s work celebrated the inherent geometric structures and repeating patterns found in nature. Drawing from his background as a sculptor and iron craftsman, he approached plants as architectural forms, highlighting their symmetry and rhythm against simple backgrounds. Using custom lenses that magnified his subjects by up to thirty times, he revealed a world of intricate details that often went unnoticed. Blossfeldt’s photographs, initially intended as scientific references, became influential works of art, inspiring photographers and artists alike. His pioneering contributions to close-up photography shifted perceptions of the natural world, unveiling its inherent artistry.

Edward Weston (1886–1959): Master of Modernism

Edward Weston (1886–1959), one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century, began his photographic journey in Chicago, where he captured images in city parks as early as 1902. His work was first exhibited in 1903 at the Art Institute of Chicago. By 1906, Weston had relocated to California, where he established a portrait studio in a Los Angeles suburb. However, it was the dramatic landscapes of the American West that soon became his primary inspiration.

In the 1930s, Weston, alongside Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, and Willard van Dyke, co-founded the f/64 group. This collective championed photography characterized by sharp focus and immaculate detail, a philosophy that profoundly shaped the aesthetics of American photography.

Weston’s achievements were groundbreaking. In 1937, he became the first photographer to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship, which allowed him to dedicate himself entirely to his art. His iconic works—meticulously printed photographs of sand dunes, nudes, cabbages, kale, peppers, rock formations, cacti, shells, water, and human faces—are celebrated for their formal brilliance and enduring impact on modern art.

Through his lens, Weston elevated everyday objects to profound works of art. His exploration of texture, light, and shadow pushed the boundaries of photographic abstraction, creating images that remain timeless benchmarks of photographic excellence. The legacy of Edward Weston continues to resonate, as his works define the possibilities of photography as a medium and its capacity to capture the sublime.